“If the tsunami warning comes,” says the attendant at the Iwate Tsunami Memorial Museum, “you must go this way.”

She points out the road to a primary school visible on high ground in the distance.

“Twenty to 25 minutes by walk,” she says.

“Ten minutes by run,” I reply.

The Iwate Tsunami Memorial Museum displays the remains of a giant steel girder from a bridge swept away by the 2011 tsunami. Photo: Peter Neville-Hadley

During eight days travelling south on foot down the east coast of Japan’s main island of Honshu, on the newly created Michinoku Coastal Trail, a friend and I have seen plenty of evidence of the destructive power of water: spaghettified rebar writhing in the remains of buildings crushed by the tsunami of March 11, 2011; towns freshly reconstructed and cowering behind newly built concrete barriers; high water marks on cliff sides several metres above our heads.

It’s a great pleasure that Japan is open for walking again, we tell the museum attendant, and after this self-guided tour we’ll be joining a small-group guided walk, conducted at a more gentle pace. But if the siren sounds we won’t be walking anywhere: we’ll be sprinting.

Reminders of the damage wrought by the tsunami of 2011 abound along Honshu’s northeastern coast. Photo: Peter Neville-Hadley

The museum commemorates what the Japanese call san-ten-ichi-ichi, or 3-11. It reminds us that human memory is shorter than the time between disasters, leading to much avoidable destruction.

After one tsunami a village may relocate to higher ground, but fishing families gradually move back nearer to the sea only to be swept away by the next great wave.

The Michinoku Coastal Trail is itself a memorial, conceived in part as a celebration of the post-tsunami reconstruction of the region, restoring and linking together sections of ancient paths to form a route hundreds of kilometres long, from Hachinohe, near the top of Honshu, down to Soma, on the coastline just east of Fukushima City.

With the help of Walk Japan’s personalised and heavily illustrated route booklet, we’re doing the self-guided version of the Hong Kong-based cultural trek specialist’s latest offering, called the Michinoku Coastal Wayfarer. This presents highlights of the trail, with long walks linked by brief rural train rides.

The walking includes stiff climbs to vermilion shrines at coastal viewpoints, descents to tidy fishing villages in barricaded coves, and seaside strolls past islands of sandstone thickly topped with pines and looking like toothbrush heads.

Much of the walk winds through shadowy forests made comfortably spongy underfoot by leaf litter, with climbs on staircases of roots. The sound of surf is off to one side and there are occasional views down steep cliffs to narrow inlets full of foaming water.

Elderly women can be seen collecting and drying kelp along a seaside section of the Michinoku Coastal Trail. Photo: Peter Neville-Hadley

Simple plank bridges cross noisily chuckling streams, sunbathing lizards dash for safety on rocky promontories, and there’s the occasional whiff of fox.

Even local people seem slow in discovering this route, as occasional invitations to click trackside counters reveal. In one case only a single walker has preceded us in the past month.

One morning a sudden barking off to the right is a welcome indication that in this thinly populated corner of Honshu, we must be approaching another village. But then a kamoshika, or Japanese serow, a grey and white fluffy creature commonly described as a goat-antelope, stocky-bodied and with stubby horns, springs onto the path.

It looks too pretty to be truly belligerent, but it barks once more, lowers its head and dashes down the track straight at me, swerving only at the last second. It reappears further down the path to bark again, then vanishes into the undergrowth.

Occasionally the route descends on newly constructed stairways intended to provide evacuation shortcuts if the tsunami alarm sounds again, and occasionally it tunnels through concrete barriers to cling to cliff sides at water level, passing rocks eroded into curious shapes by the waves.

In one town the mayor is now feted for having pushed through the timely construction of a barrier despite local opposition. In another, the cement mixers are still helping to build the protection against the waters the locals wish they’d had earlier.

Many coastal towns in northeastern Honshu have built tsunami defences to protect against future disasters. Photo: Peter Neville-Hadley

But everywhere there’s a warm welcome for the return of foreign visitors, never numerous in this part of Japan but non-existent after the wave of Covid-19 broke worldwide.

As on all of Walk Japan’s trips there’s frequent use of small-scale, family-run traditional accommodation that provide vast multi-course meals full of pleasant surprises to those whose previous experience of Japanese food has been only in restaurants.

On the Michinoku trail there’s seafood in great variety, from the freshest sashimi to three-day stewed swordfish head. On the last evening, the Nine One restaurant, in Kesennuma, a fishing town heavily hit by the 2011 tsunami, provides an Italian meal with strikingly well matched sake pairings.

Traditional family-run inns are a staple of rural Japan. A multi-course feast of regional specialities is usually included in an overnight stay. Photo: Peter Neville-Hadley

The walk’s guidebook is detailed, and the accommodation, baggage transfer and the occasional taxi pickup are all arranged in advance, so it would be possible to do the trip entirely solo, even without two words of Japanese to rub together. But friendly bickering over directions, and whether to take longer or shorter alternative routes suggested, is part of the pleasure.

There’s a sense of achievement as each waypoint is reached, although reading the detailed background information, and dealing with navigation rather than simply being led, can be a distraction from purely taking in the views.

First-time Japan walkers might be wise to begin with a guided, small group (up to 12) tour so as to gain initiation into the intricacies of inn etiquette.

On Walk Japan’s San’in Quest, a guide details the local history. Photo: Peter Neville-Hadley

One candidate could be Walk Japan’s recently revised San’in Quest, which runs across western Honshu from Yamaguchi, in the southwest, to Matsue, in the north, before swinging back to Hiroshima.

It links many towns and villages rarely visited by foreigners, whose ruling families in the 19th century played a role in the overthrow of the shogunate and the restoration of imperial rule in 1868.

The walking is less strenuous, although it includes a climb of Japan’s smallest volcano and the crossing of several low passes. But breaks for historic houses, ancient workshops and castles are frequent, with each day full of surprises, and no two alike.

The route down into the old town of Omori passes shrines and graves of 17-19th century silver miners. Photo: Peter Neville-Hadley

This is the region historically known as Chugoku – the same characters as for China, but here meaning “province in between”, referring to its location between the productive agriculture of Kyushu to the west and the capital region to the east.

The broad, cypress-shingled pagoda at Rurikoji, built in 1442 and five storeys high, is evidence of Yamaguchi’s former wealth, gained from trade with China.

But the inn at Yuda that night, a century-old house, all traditional tatami matting in the rooms but with Europeanised 1930s furnishings in the public areas, is nearly as magnificent, its gardens featuring trees planted by visiting emperors, and ponds with carp like aqueous cats, willing to be fed by hand.

The five-storey pagoda at Rurikoji temple, established in 1442, is one of the oldest of its kind in Japan. Photo: Peter Neville-Hadley

One day is spent crossing a limestone plateau through waist-high grasses, past tiny pockets of agriculture in the water-collecting depressions formed from the collapse of caves beneath, before descending to pass through illuminated underground spaces.

Another day’s walk partly follows the ancient route local lords and their retinues were obliged to take to pay homage to the shogun in Edo (now Tokyo), beggaring them and reducing their ability to rebel. At one low summit there are still stone-enclosed resting points for the lords’ palanquins.

On the descent into Hagi, an old castle town, there’s a visit to a private school established in the 1840s, now preserved as a museum, where for 30 years a critic of the shogunate taught some of those who would restore the emperor and subsequently serve as ministers.

Inasa beach in Izumo is the site where, it is believed, Shinto’s eight million gods come ashore every year. Photo: Peter Neville-Hadley

Other highlights include observing clouds of kites over a tidal pool full of trapped sea creatures, and a walk up through long corridors of vermilion torii (gates) and then through a camellia forest to the stone platform of a now-vanished castle, with views down to the Taikodani Inari shrine and the small town of Tsuwano in its narrow valley.

At Yunotsu, an old fishing port and spa town, one of many ancient houses harbours a state-of-the-art launderette, and hidden through that a taco bar.

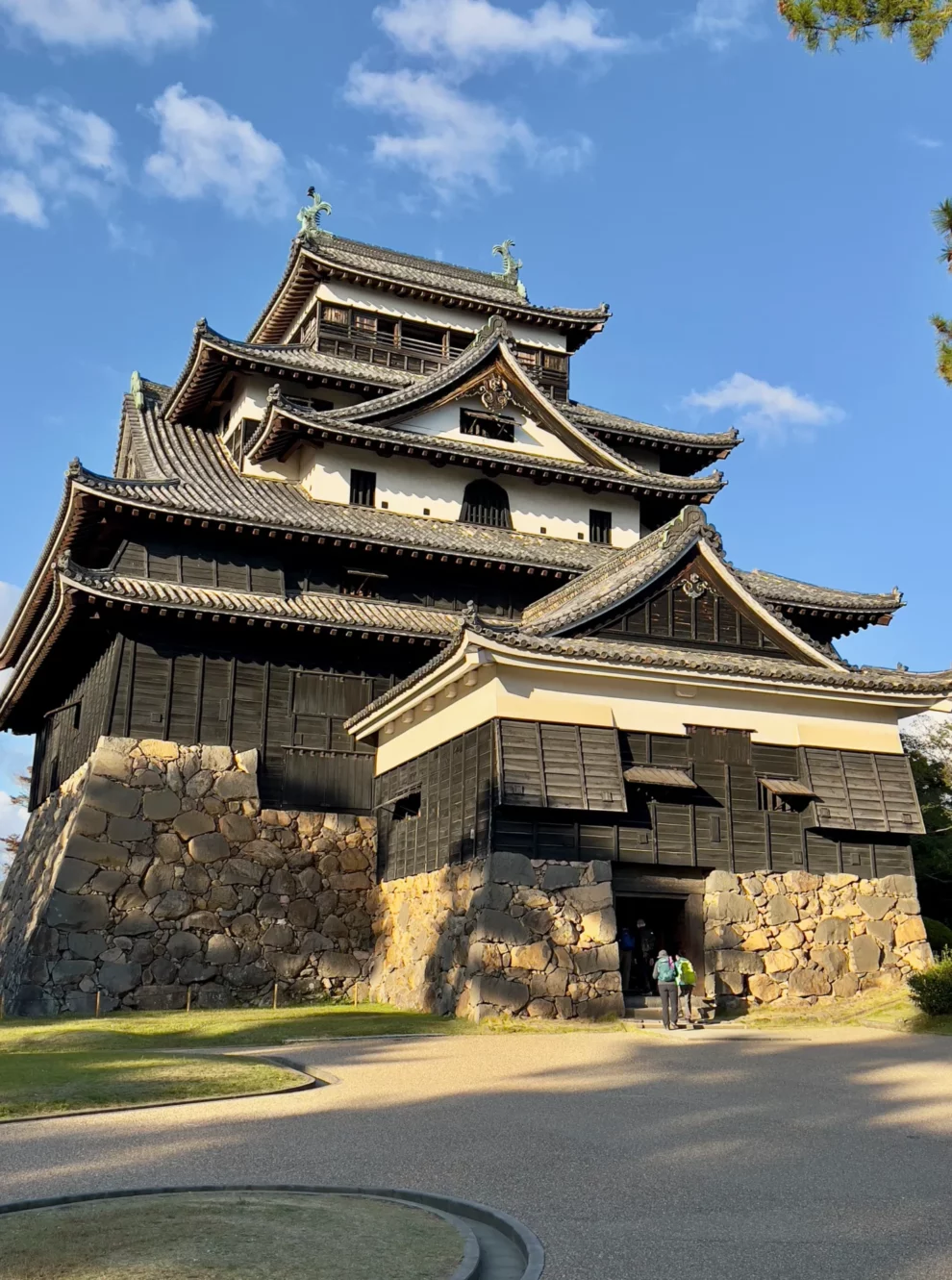

Tsuwano features a row of sake brewers, Matsue the climbable donjon of one of Japan’s surviving castles, and Izumo a vast shrine complex where each year in the tenth lunar month 8 million Japanese gods supposedly come to take their holidays.

The castle at Matsue, in Japan’s Shimane prefecture, was built in the 17th century. Photo: Peter Neville-Hadley

But whether the walk is a strenuous hike or a more steady stroll with plentiful contemplation of culture, there can be no better balm for the muscles than a daily soak in often geothermally heated waters, followed by a meal of huge variety taken in traditional yukata cotton gown and haori over-jacket.

source: scmp